By Maren Madalyn, contributing writer

Whenever I hear educators ask for examples of effective family engagement, I have to chuckle. Not because this is a laughing matter — family engagement in schools is essential and yields positive student outcomes like improved attendance, higher grades, and even better student behavior. I chuckle because the question is both common yet incredibly nuanced. Family engagement comes in so many different forms, each unique to the school and its community members.

For some schools, engagement looks like learning stations at a Back-To-School night, where parents discover local resources that can help meet their basic needs. In other communities, educations meet families where they are in the community through a series of town hall meetings, so families can share their concerns about school climate, academic goals, social-emotional learning, and other important topics.

Rebecca Honig of ParentPowered and Jessica Webster of the Mid-Atlantic Equity Consortium recently offered a powerful webinar unpacking how educators can boost the effectiveness of family engagement efforts. When asked how they defined ‘family engagement’, their response was simple.

“Family engagement is best thought of as a collection of habits. It’s all about the things that educators do each and every day that build a meaningful relationship between schools and families.”

Jessica Webster (MAEC) & Rebecca Honig (ParentPowered)

The power of habit for family engagement in schools

Before we dive into those habits, let’s remember why families are so critical to student success.

As the National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement (NAFSCE) describes, family engagement is “a shared responsibility… to reach out to engage families in meaningful ways and in which families are committed to actively supporting their children’s learning and development.” It’s this shared partnership that fosters supportive learning environments that ensure the success of students from all kinds of backgrounds.

Research has shown that there is a positive relationship between family engagement and a swathe of educational outcomes. These include increased academic achievement, increased attendance rates, higher graduation rates, and even boosted teacher satisfaction.

So it’s no wonder that educators want to understand how to design effective, systemic family engagement strategies within their communities!

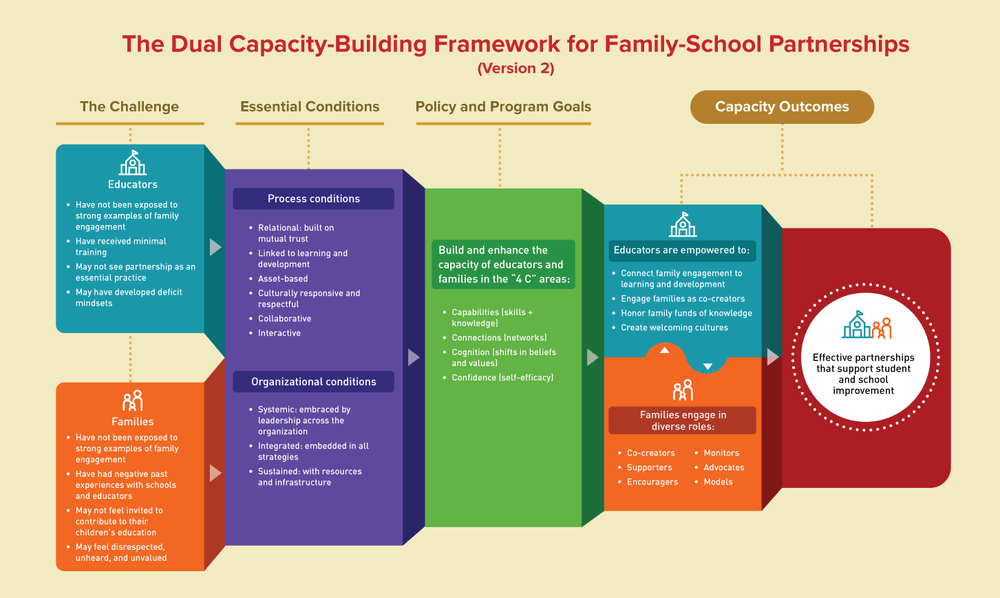

Essential conditions of effective engagement

One of the most commonly referenced models for effective family engagement comes from Dr. Karen Mapp of Harvard University. Her Dual Capacity-Building Framework emphasizes essential conditions that, when adopted, help educators lay the groundwork for building strong connections with their families. According to this model, effective family engagement strategies must be:

- Culturally responsive and respectful

- Collaborative

- Interactive

- Relational and built on mutual trust

- Linked to learning and development

- Strengths-based

But there are SO many ways in which district and school leaders can apply these principles to parent involvement in schools. It can be challenging for staff and faculty to know exactly where to begin, too. What changes do we introduce to our existing school programs? Is there room for traditional practices like parent-teacher conferences? How do I decide what data to review to understand and report on the impact of our family engagement approaches?

An educator’s heart rate might spike just thinking about all these questions around family and parent engagement.

But Honig and Webster have great news here: educators don’t need to make radical changes to family engagement programs to develop strong relationships with families, right now. They emphasize that by building positive habits of engagement, school teams can, little by little, cultivate these essential conditions of family involvement.

And it makes sense — habits are defined as “settled or regular tendencies or practices, especially ones that are hard to give up.” That’s exactly what makes them so powerful for parental involvement in schools. Building habits around family collaborations makes these practices of partnership as natural as breathing and drinking water — so much so that teachers cannot imagine student learning happening without family involvement in school.

It’s not about driving huge changes but rather introducing micro-practices into an ecosystem that build momentum toward reciprocal and deeper partnerships. And it’s these kinds of family-school partnerships that make learning possible!

5 habits for effective family-school partnerships

Drawing on their immense expertise in family engagement, Honig and Webster identified a series of high quality practices to support educators building those habits of partnership. Let’s take a closer look at five of these habits and ways to bring them to life — through existing, commonly used family engagement strategies in schools.

#1: Building the habit of reflection

From the moment a parent first sets foot on campus, educators begin building that parent’s trust in their school. But even the best strategies for equitable family engagement take time and consistency to unlock that family capacity to bolster their student’s development and academic success.

Honig highlights that a habit of pausing to reflect can help teachers steer their interaction and communication with families towards cultivating relational trust that drives positive results. When we pause and take a step back to re-examine our actions with parents, we have the opportunity to validate that our actions are effectively engaging families and moving that partnership forward.

Even just a few moments of reflection can be transformative for the relationship between an educator and a family, and even help strengthen a family’s protective factors as emphasized by trauma-informed education. That way, educators create a safe, inclusive environment for all members of the community, regardless of their background or past experiences.

Honig suggests starting with these questions, the same that ParentPowered uses to guide all outreach through ParentPowered programs to families across the country:

- Is this communication accessible?

- Is it inclusive?

- Is what I am asking families to do doable?

- Is my communication strength-based? How does it feel for a parent to receive it?

Example: reflections before sending an email

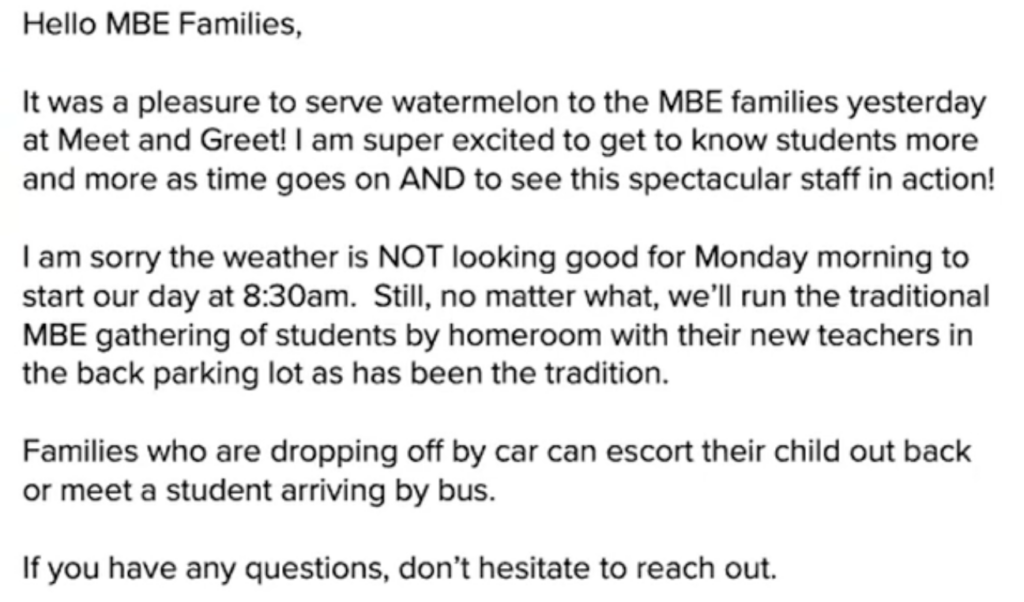

Written communication, such as school newsletters or emails out to families, offers an easy opportunity to practice the habit of reflection. Here are three reflection strategies to support educators in preparing communications out to families, ensuring the touchpoint contributes towards building their relational trust and sense of belonging:

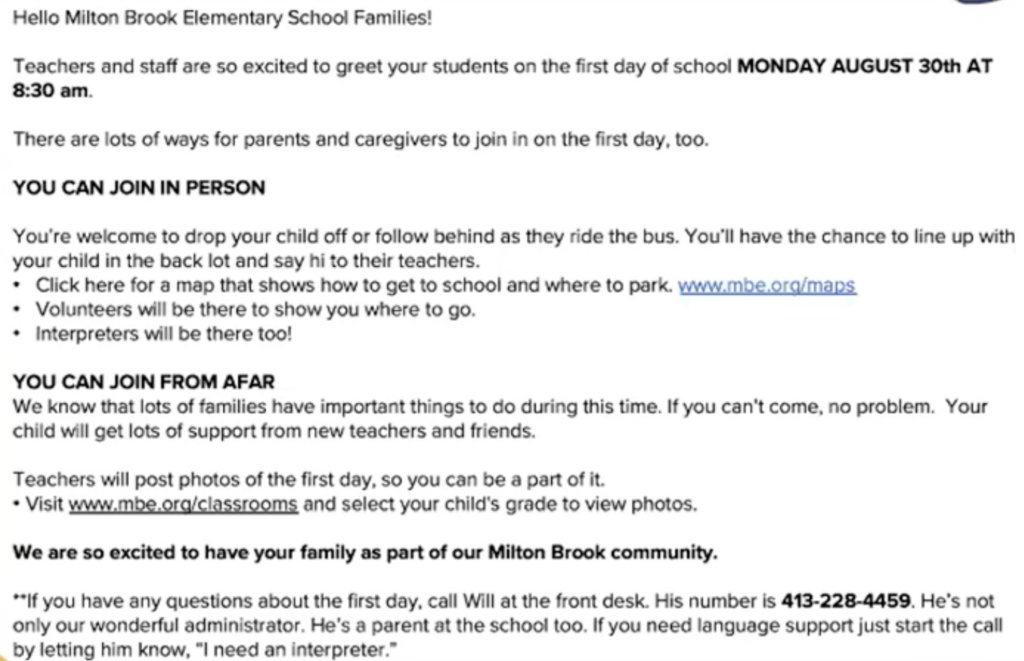

- Watch out for “insider” language or references. Using acronyms, nods to specific school events without context, and other “insider references” can create confusion for families who are new or unfamiliar with your school’s culture. Honig recommends that school personnel use language that can be understood by all members of the community, making things like school names and event purposes explicit.

- Offer multiple avenues for parent involvement. When describing school processes to families, educators should consider how their school educates families on all the available options for following that process. For example, many families might choose to drop off students in-person for the first day of school, but some families may be unable to do this for a variety of reasons. School faculty can tell families about available alternatives that also ensure their child has a welcoming and fun first impression.

- Give clear instructions to parents about contacting their school. Honig and Webster emphasize that it’s critical for educators to be explicit about how, where, and to whom families should connect, depending on what they need. For example, if a parent has questions about how to enroll their child in free and reduced lunch programs, tell them exactly what number to call and who in the front office to speak with. For multilingual families, Webster suggests posting resources in a family’s home language around the school front office. A visiting parent can point to one of these signs and signal to office staff that they need help with translation.

These two example emails below demonstrate the habit of reflection in action. The author, a school administrator, paused after crafting the first draft on the left, and reflected on its content. They then revised the email to up-level the inclusivity and clarity of this outreach, ultimately sending out the draft on the right.

BEFORE

AFTER

#2: Building the habit of (active) listening

When people believe that they are seen and valued, they are more likely to share information and feedback with others. Educators and staff members who engage families by seeking feedback from parents can gather valuable insights about students, which in turn, empowers them to perform their roles more effectively. As Webster explains, the habit of active listening is one of the most powerful habits that an educator can build for improving school climate — and at times, it’s one of the hardest skills to practice.

Active listening is a series of communication skills that result in clear, honest, and respectful information exchange between two individuals. Here are a few skills involved in practicing active listening:

- Asking open-ended questions

- Using neutral body language such as resting arms down at the side

- Remaining curious and open-minded — even when hearing information or feedback that reflects views different from your own

Example: letting families lead conversations

The parent-teacher conference (or as Webster calls it, a family conference) is an excellent starting place to practice the habit of listening.

At any parent meeting, Webster encourages teachers and school leaders to elevate family voices by allowing the parent to speak first. Giving opportunities for families to share their goals, beliefs, concerns, and questions about their child’s education sets the tone from the start that parental engagement is as crucial as student engagement.

The habit of listening is especially important early in the school year, when teachers may not have a lot of information about a student. Centering families as partners in this conversation opens the doors for future exchanges to be as productive and fosters mutual respect. Steward recommends building in extra time to these meetings to ensure staff are not rushing between them. Even just 5 minutes can make all the difference!

No matter where or when educators converse with families, it is possible that some conversations become especially challenging. When families or educators feel upset or frustrated, it can make conversations more challenging and less collaborative. However, Webster reminds educators to turn to active listening and other restorative justice practices to both de-escalate a tough conversation and leverage them as opportunities to deepen trust with families.

#3: Building the habit of visible learning (aka sharing)

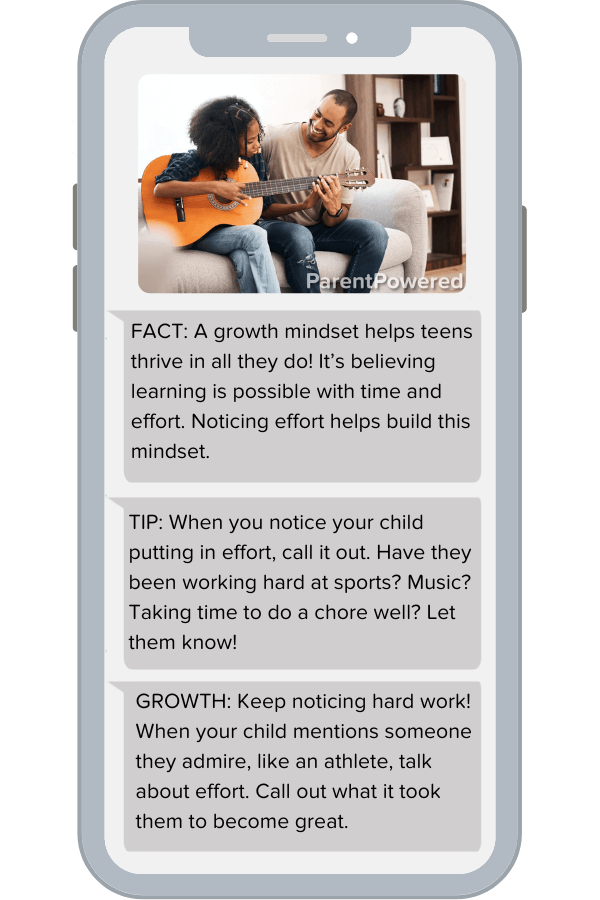

In her framework, Dr. Mapp highlights that “linking engagement to learning” is essential to cultivate a positive family school partnership. On-campus family events certainly give parents the opportunity to walk in their students’ shoes and gain exposure to a student’s learning environment. But Honig and Webster remind educators that these events may not be accessible for all families. Further, families don’t need to wait for the next school program on-site to witness their child’s learning in action.

Webster further clarifies that educators can engage in regular habits of sharing through two-way communication — meaning families are communicating with their schools as often as schools are communicating with their families — to make learning accessible and visible.

Example: repurposing the take-home folder

Inspired by our recent interview with a parent engagement specialist, the take-home folder is an excellent entry point for building the habit of visible learning with your families. Typically these tools are used for sending assignments, homework, and resources home to families. But Honig explains that teachers can flip the take-home folder on its head by encouraging families to share information from home to school, too, getting them actively involved.

For instance, Honig suggests putting prompts for families inside students’ homework folders, ones that encourage parents to answer reflection questions or log observations about their students learning at home. For families that don’t speak English natively, educators can use visuals as an alternative prompt for engaging families more, such as using feeling faces or other cues.

#4: Building the habit of partnership

It may seem obvious that the habit of partnership and involving families is essential for, well, family-school partnership. But what makes a partnership most effective? And how do educators tap into the unique role that parents, caregivers, and guardians play in student learning?

Honig recommends starting with reflection on existing relationships with each family. She offers these questions to guide educators through this reflection process and to identify what each side of the relationship brings to the table to aid in student growth:

- What parent skills might complement or support classroom goals?

- What skills can parents build at home?

- What skills or practices map onto daily routines?

- What is a doable strengths-based way that parents can practice these skills?

By taking a moment to identify the strengths and expertise that each parent and educator bring to the table, school leaders can then identify specific, doable, and strengths-based engagement opportunities for parents. That way, they can participate in a student’s educational experience within their existing family capacity.

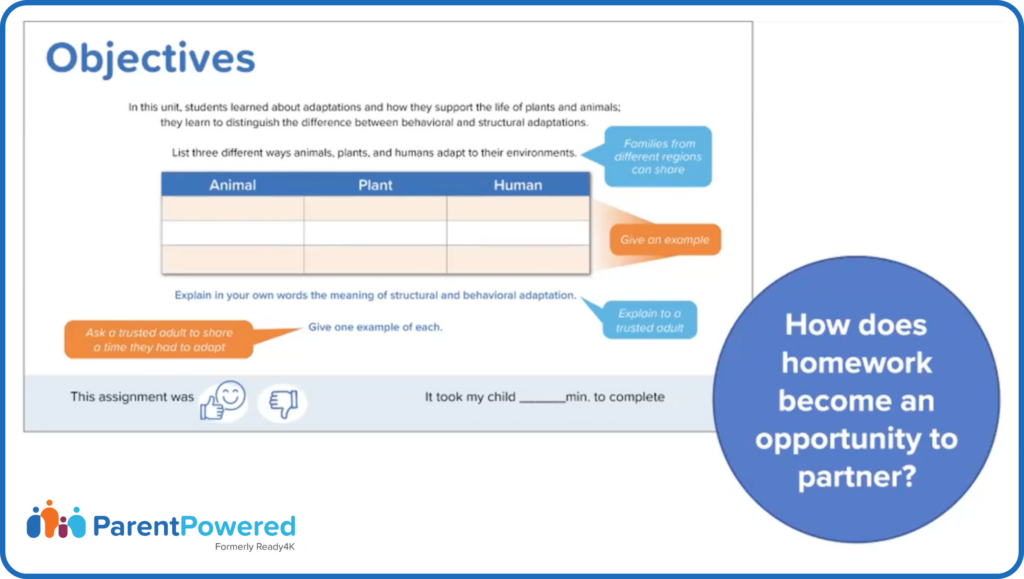

Example: guiding parents with homework help

Homework is a highly visible, and sometimes only, view point that a parent has into their student’s learning journey. It is a data point for families to see how well their kids are digesting what they are studying in the classroom. Homework also offers a huge opportunity for families to take an active role either directly or indirectly, in student learning.

Below is an example homework assignment sent home with a twelfth grade student. The original assignment is pretty straightforward, but it does not invite clear ways for parents to participate in that assignment.

Honig highlights simple but effective revisions that might clarify the role that a parent can play in this student’s at-home learning:

- Include a prompt for the student to include examples from different environments. Families living in different regions can identify examples from their personal experiences.

- End the assignment by asking the student to share what they have learned from the assignment with a trusted adult at home.

- Add reflection questions specifically for the parent inviting them to share their observations of how well the student did on the assignment. For example, what emotions did your child show while doing the assignment? How long did it take your child to do the assignment?

In older grade levels, parental engagement might need to look different to be more effective in supporting student academic success. Research has shown that middle school students perform worse on homework assignments when adults give direct aid and feedback — and yet this kind of support may feel natural for a parent to want to give to their child.

But Honig shares that educators have an opportunity to coach middle school parents in providing indirect support on homework to make parental involvement and student learning more effective. For example, instead of directly trying to solve a math problem with their child, a parent can instead encourage their own child to ask further questions or identify experts in their educational environment that could help them solve their own problems.

By baking family partnership opportunities into students’ homework assignments, teachers scaffold parent engagement in student growth and make learning visible.

#5: Building the habit of evaluating and following Up

Habits stick most strongly when we see the positive results of practicing them. This is true regardless of the habits we are building. For family and community engagement in schools, it also means that educators must participate in processes of continuous improvement. As Webster describes, building a habit of evaluating and following up is not just about reinforcing the other four habits — it’s also about finding new opportunities to iterate upon them for bigger impact.

Continuous improvement means that educators collect data from their stakeholders on a regular basis, using the information to understand the impact of family engagement strategies. Webster also reminds educators to celebrate what is working in parallel to tweaking what needs improvement. This is not a one-time event, but rather an ongoing cycle of evolution and communication throughout the school year.

Example: intentional family feedback surveys

Data is a crucial component to building a process of such continuous improvement.

Family feedback surveys offer educators a quick and simple way to gather information about parent perceptions, concerns, goals, and other crucial insights that might benefit student learning. An effective family feedback survey is accessible to every member of the school community — even those harder to reach families that don’t often attend school events or are otherwise less communicative.

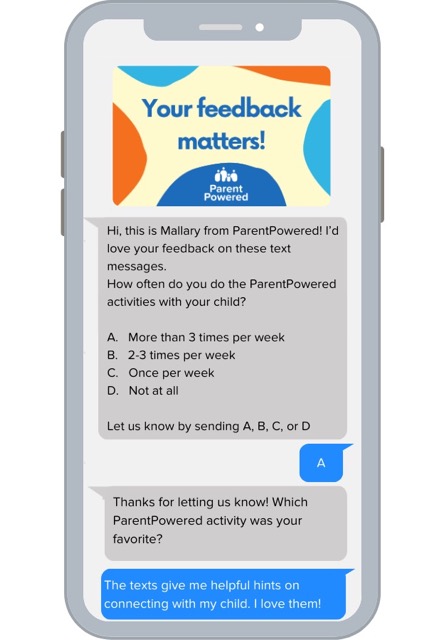

ParentPowered allows schools and other community organizations to send customized surveys throughout the year to quickly gather input via text message from families that have crossed their community. These surveys can be translated into multiple languages too, which is critical because family feedback surveys are especially useful for engagement with multilingual communities.

Honig offers a few tips for building a family feedback survey and ensuring all family members have the opportunity to participate:

- Know your what/why/how. educators should make sure they are aligned on what they need to know from families, why they need this information, and how they plan to utilize family input in children’s education. This will ensure educators collect valuable and usable feedback — and also signals to families that their voices matter.

- Use the right type of question for the info you need. Knowing the what, why, and how will help school staff pick the right kind of question to source and analyze the data they need. For example, if educators are deciding which of four possible topics to highlight at an upcoming family workshop, they might prefer a multiple choice question over open-ended questions.

- Show families the impact of their data. This is absolutely essential to ensuring surveys don’t remain one-way communication! A simple email sharing the results of that multiple-choice survey on family workshop topics shows families how their feedback impacted school decisions.

- Build inclusive practices. Educators want all parents responding so that their decisions reflect all families. Translating surveys, leveling text to a third-grade reading level, and using shorter sentences are just a few ways to make surveys more equitable and accessible for everyone.

Habitual family partnership deepens student learning

In the end, both Honig and Webster agree that these habits of effective family involvement are just the tip of the iceberg of possibilities. Family engagement comes in so many different flavors, each reflective of the diverse communities it benefits.

But what matters most is this: where there are trusting, reciprocal relationships among critical adults in a school community, there is student success. And this is what I find so remarkable about blending habit-building with family engagement.

Educators need not recreate their entire family school engagement programming from scratch in order to tap into their community’s potential to boost student learning. Instead, through small, iterative changes and habit-building practices, educators help families unlock their potential for student learning.

About the author

Maren Madalyn has worked at the intersection of K12 education and technology for over a decade, serving in roles ranging from counseling to customer success to product management. She blends this expertise with fluid writing and strategic problem-solving to help education organizations create thoughtful long-form content that empowers educators.