Understanding Equity in Education

Equity in education has become a common goal and guiding principle for modern school improvement and education reform efforts in the United States. [1], [2], [3] According to Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis, “[t]he achievement gap between racial minorities and whites as well as between the rich and the poor is one of the prominent issues of modern American education” [4].

Promoting equity can involve a wide range of school-based strategies, from creating an inclusive classroom to reducing barriers for students with respect to transportation. But families are just as essential to include in any efforts to create equity within the educational system.

Since equity is at the center of so many educator conversations, let’s define exactly what is meant by “equity in education” vs. equality.

Educational equity is achieved when all students receive the resources, opportunities, skills, and knowledge they need to succeed in our democratic society.

American Institutes for Research (AIR) [5]

Equity is the attainment of comparably positive outcomes for all groups within, or served by, any complex system through implementation of policies, practices, and procedures that remove systemic barriers and provide the supports needed to ensure everyone’s full and successful participation in the system.

Equity—the state that would be achieved if individuals fared the same way in society regardless of race, gender, class, language, disability, or any other social or cultural characteristic.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) [6]

Educational equity is the intentional allocation of resources, instruction, and opportunities according to need, requiring that discriminatory practices, prejudices, and beliefs be identified and eradicated.

National School Board Association (NSBA) [9]

Equity does not mean giving everyone the same thing. Equity means giving each student whatever resources and support they need to optimize their learning and achievement.

Mid-Atlantic Equity Consortium (MAEC) [7]

Educational equity means that every student has access to the educational resources and rigor they need at the right moment in their education across race, gender, ethnicity, language, disability, sexual orientation, family background and/ or family income.

Council of Chief State School Officers / The Aspen Institute [10]

These sampled definitions of equity in education share a theme: Ensure access to resources and opportunities for all students. That way a student from a low-income family is just as likely to succeed as a student from a more affluent background, and a student of color is just as likely to succeed as a white student.

Educational equity is achieved in a world where “every child, regardless of circumstances at birth, has the ability to reach their full potential” [11], a world without a “performance gap due to race, gender, family income, disabilities, resource allocation, [or] other factors” [4].

These six definitions describe an equitable education as both universal (accessible by all) and personalized (tailored to meet individual needs). The goal of equity is a universality of access to outcomes—we want all students to have the opportunity to thrive and succeed. The process to reach this goal involves personalization—we want to support each student according to their own situation, ensuring they have the same opportunities to succeed.

Inputs and Outputs

Inputs and Outputs

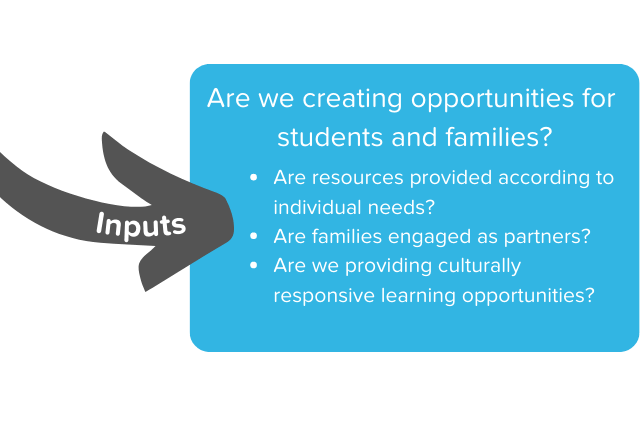

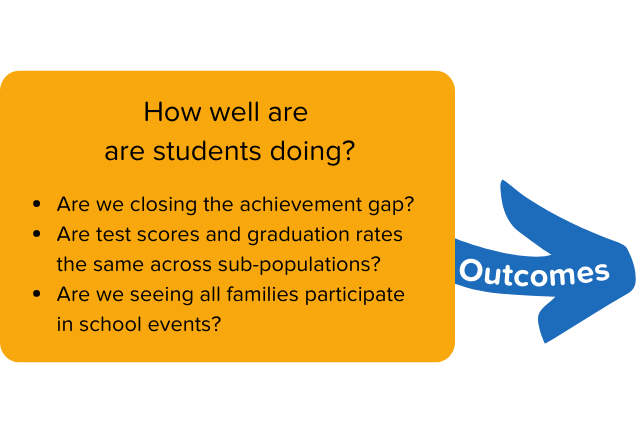

As schools work towards equity, it is important that they formulate and evaluate growth opportunities through two lenses: inputs and outputs. In looking at inputs, we evaluate our curriculum and instruction, the systems we have in place, the opportunities for engagement, and the overall learning environment.

The following questions help us reflect on strengths and areas for growth related to inputs:

-

Are resources provided according to individual needs?

-

Are families engaged as partners?

-

Are we providing culturally responsive learning opportunities?

But inputs alone are not enough. We must also look at what happens as a result of those systems, experiences, and opportunities (those inputs) by evaluating outcomes.

These questions help us understand what happens (what outputs occur) as a result of our efforts:

-

Are we closing the achievement gap?

-

Are test scores and graduation rates the same across sub-populations?

-

Are we seeing all families engaged in student learning?

According to the Learning Policy Institute [12], critical elements of an equitable educational system include:

-

The quality of teachers and teaching

-

The development of curriculum and assessments that encourage ambitious learning by both students and teachers

-

The design of schools as learning organizations that support continuous reflection and improvement

In reality, there are many barriers to students receiving and being able to benefit from high quality education, including but not limited to:

-

Trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) [13]

-

Poverty

Adult stakeholders must work to break down or help students overcome these barriers in order to achieve equity in education. [14]

Equity and Equality

What’s the Difference Between Equity and Equality?

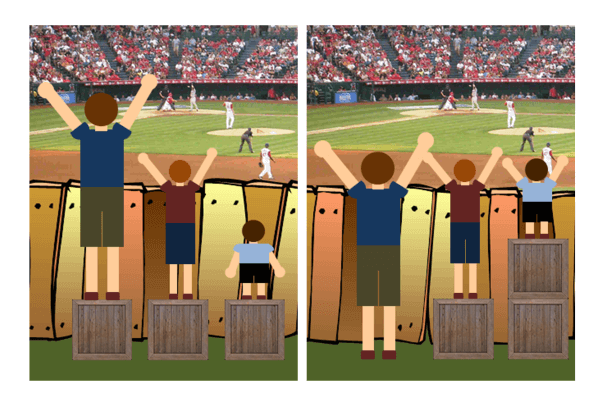

Though similar, equity in education is not the same as equality. Equality is giving everyone the same treatment and resources, whereas equity is giving to each person what they need to have the same opportunity to succeed as everyone else.

Equality

-

Same resources and opportunities for all students

-

Students receive same quality of education as all other students

-

Evaluated by inputs

Equity

-

Resources redistributed to close the opportunity gap

-

Students receive quality education adapted to their needs

-

Evaluated by inputs and outputs

This classic image [15] has been widely used to illustrate the differences between equality and equity or justice. The spectators in the left panel each stand on one box—equality. However, the shortest one cannot see the game at all, the medium-height individual can just see over the fence, and the tallest individual can easily see over the fence. Each person has been given the same number of boxes (representing resources), but not necessarily the right number of boxes to allow someone of their height to see over the fence.

In the right pane, by contrast, the boxes are redistributed in a way that enables each spectator to see the ball game. Even though the resources are not distributed equally, they are distributed equitably because everyone has what they need according to their own situation.

An equitable approach acknowledges that disparities exist and addresses them so that everyone has a fair chance to succeed.

See Why Educators Love ParentPowered

Take a self-paced tour of the ParentPowered programs to answer questions like:

- How does the evidence-based methodology work?

- What do the families receive each week?

- Which skills and content areas are covered in each curricula?

- How do the curricula support classroom learning?

- What does the implementation process look like?

- What kind of data and reporting is included in the program?

Take the Tour

Why does equity matter for student outcomes?

Equity in early childhood education and K12 learning can have a profound impact on student success. When educators and other community stakeholders take an equity lens to their work for students, ensuring equally high outcomes, it makes a difference in students’ well-being, learning and academic achievement.

Here are some examples of equitable practices in education that have been shown by research to improve learning outcomes:

-

Diversity and representation in the educator workforce

-

Diversity and representation in the curriculum

-

Culturally responsive practices

-

Trauma-informed practices

-

Community Schools

-

Addressing racial bias of educators

-

Parent education designed especially to reach traditionally “hard-to-reach” groups like low-income families, families of newcomers, and families who speak languages other than English

According to NAFSCE, “High-impact family and community engagement is collaborative, culturally responsive, and focused on improving children’s learning” [16].

Some might think about equity examples in education in terms of fairness in the process of giving students what they need to succeed based on their background (inputs). Others might focus more on what happens as a result, in terms of student achievement or other metrics (outputs or outcomes). It’s important to note that equity is about both.

What are common challenges in achieving educational equity through family engagement?

Decades of research have shown that family engagement can be instrumental in achieving equity in education, because families of all backgrounds are interested in their children’s success and capable of supporting their learning and growth. However, even with this motivation and potential, parents may have a difficult time knowing where to begin to support their child’s academic success, especially if the school has not oriented them to key academic goals and indicators.

Some types of high-quality programs that schools can offer for parents are expensive and hard to access. For example, family workshops can be highly engaging but tend to attract families who have the extra time and mobility to attend in-person events. (This is why ParentPowered is designed from the start to be in a format that families can use on the go—text messaging.)

Because it takes resources to get resources, families who already have the most advantages are usually the ones to get access to effective tools. In addition, under-resourced districts that could benefit the most from family engagement may not have the means to fund a family engagement coordinator or set up other infrastructure to involve families.

Creating authentic partnerships between schools and families is a complex and multifaceted task. According to WestEd [17], challenges include the following:

-

Family engagement activities are often isolated from other initiatives in districts

-

Family engagement staff in districts often work in a silo, not in collaboration with other departments

-

Families of low-income students and families of students of color are often underrepresented in engagement activities

-

Educators struggle with how to evaluate family engagement programs and activities, beyond tracking the number of participants attending events

An additional challenge noted by the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments [18] is that caregivers “who do not speak English or who were educated in other countries may be unfamiliar with expectations for American school involvement.”

With dedicated, thoughtful family engagement work and effective support systems, however, these challenges can be overcome.

How does family engagement increase equity?

Decades of research show that equitable family engagement is a fundamental component of student success and school improvement. In fact, up to 80% of the variation in students’ performance in public schools results from home-related rather than school-related factors [19]. When caregivers, schools and communities work together, students’ attendance and grades improve. This has held true for students of all ages, backgrounds, and ethnicities.

Researchers have found that:

- Parents’ high expectations for their students’ academic performance predicts academic achievement [20].

- Attendance at on-campus meetings and communicating consistently with important school personnel predicts academic achievement [21].

- Children whose parents received texts messages breaking down the complexity of supportive parenting demonstrated a significant boost in literacy skills [22].

- Family engagement improves school attendance [23] and completion [24].

Family engagement can also influence a school to make positive changes, especially for students with minimal economic resources or facing inequity. When schools understand the economic challenges or other barriers to well-being that families face, they can provide better support and resources to help students succeed. The synergy between family well-being and student success is a main reason why community school partnerships are so effective.

Additionally, when a school learns more about the family and child through parent engagement, the school can then adjust instruction and class materials to better reflect the child’s identity. As a result, students see themselves in their learning.

Family engagement is also being embedded into state and district equity policies. For example, see section II. A. of this Washington state school district’s Race and Equity Policy [26].

In the end, equity in education is “a shared effort of the entire education community in caring for the diversity of students” [25], so that each and every one can succeed.

Equitable family engagement

To understand how to apply an equity lens to family engagement, let’s look at two common family engagement activities, on-site workshops and community meetings.

A district taking an equality approach will focus on inviting every family to a parenting workshop to support their children’s literacy development at home. Every family now has the same resource, which feels like a fair strategy.

In contrast, a district taking an equity approach will say, “Not so fast!” Some parents may lack the time, transportation, or means to afford childcare to be able to attend. Therefore, they don’t actually have access to the workshop. This district will look for ways to empower parents as literacy partners, regardless of whether they attend an in-person workshop. The equity-focused district sees barriers to access as barriers to equity, because they reduce the educational opportunities available to students.

To better understand what it means to remove common barriers to equity and create an inclusive learning environment, here’s how ParentPowered puts equity into action with our programs.

Essential Considerations for Equitable Family Engagement

Putting Equity into Action

Time

Do families have time to participate in their child’s education?

Information is distributed through text messages, which are limited to 160 characters each. This means that it only takes a minute to learn a parenting tip or a fact about child development.

In addition, the activities are suggested to fit into existing daily routines rather than requiring a family to set aside extra time. Folding laundry is a great time for a 4-year-old to learn about patterns that can prepare them for academic achievement in algebra later on. Bath time is a great time to practice rhyming with a toddler, which can set them up for success in language development and reading later on.

Materials

Do families have everything they need to follow our recommendations?

ParentPowered suggests quick and easy activities for families to use at home to practice math, literacy, and social emotional skills. These activities never require additional materials, just the people, places and things that already exist in a family’s life.

Families don’t need any equipment beyond normal household items to create educational opportunities. Kids can practice shapes by going outside and drawing in the dirt with a stick.

Internet Access

Will families need internet access to participate in our family engagement programs?

Millions of families in this country do not have reliable, adequate internet access [27]. About a quarter of Americans do not have broadband internet at home [28]. By contrast, 97% of Americans have cell phones [29], and 97% of cell phone users send and receive texts [30]. In fact, traditionally underserved adults text with the highest frequency.

Language

Will families be able to understand our communications and use the resources we provide? Will we be able to understand their responses?

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 350 languages are spoken in this country [31]. At the district level, it’s common to serve significant groups of families speaking 10 or more different languages, especially in urban districts. ParentPowered’s content is available in 10+ languages and counting.

Custom messages and survey questions are translated into home languages, such as Spanish, Arabic, and more. Survey responses then are translated into English for the school team.

Culturally Responsive

Are we taking cultural factors into account when reaching out and in how we offer resources?

Our country is home to families from all around the world, from many different cultures. The principle of inclusion means that family background should be an asset, not a reason that family can’t connect with valuable resources.

The content creators of ParentPowered work with experts to review and version messages for cultural appropriateness and to ensure that activities resonate with all different lived experiences.

Another way to advance equity in education is to tailor support to the specific needs of families and children.

For example, ParentPowered Personalized Learning sends facts and tips to caregivers tailored to their child’s developmental level and needs, based on data from the child’s developmental screener results. Research shows this personalized approach is far more effective to improve literacy outcomes [32].

Further, educators can offer ParentPowered Trauma-Informed to caregivers of children who may have lived through ACEs or experienced trauma.

Both of these are examples of providing differential services based on differential needs (equity), rather than the same services to all students and families (equality).

However, family engagement is not just about providing services; it’s a two-way relationship where schools share power with families.

According to APIA Education Leaders, “Community partnership is not the input phase of your planning process. It’s not the rubber stamp or seal of approval once everything is printed and ready to execute. Engaging your community is the beginning, middle, and end of the work” [33].

Inviting families to the table from the very beginning allows them to better advocate for what their child’s needs and to partner with schools to meet those needs. Instead of designing for students and the community, we design with them.

ParentPowered enhances the family feedback loop through providing families with strategies for connecting with supports and curriculum content that offers ideas and encouragement for families to reach out to teachers and administrators. We also survey families every quarter and provide partners with survey results, so they know how their families feel about their family engagement program.

“We’re talking about having families not sit across from us, but with us, making decisions about our schools and communities.”

Build Equity

How can educators build an equity in education mindset through professional development?

Although specific equity goals may differ from district to district, a level playing field is ultimately the goal. When discussing the importance of equity in education, school and district leaders are often looking for ways to create an environment in which all adult stakeholders are able to provide every student with access to a rich and rigorous education that meets their learning needs.

It’s one thing to discuss ideas related to equity. The question is how educators put these ideas into practice, be it through professional development and or shifting learning environments.

1. Notice and Address Disparities

Even if all students are meeting a minimum standard for achievement, it’s important to check for differential performance of underserved students.

In 2019, the National Research Council’s report “Monitoring Educational Equity” recommended the creation of a national system for measuring educational equity. The 16 indicators that they recommend for measuring equity are related to disparities in access to educational resources of disparities in student outcomes, such as “Disparities in Performance on Tests” and “disparities in Access to and Participation in High-Quality Early Childhood Education” [34]. Any time differences in access or outcomes are found to mirror membership in a minority or vulnerable group (e.g. children experiencing poverty, children of color, children who are dual language learners, etc.), there is a potential equity issue to be investigated.

For example, if a district staff member reviews the list of attendees of family engagement events for the past year and finds that only 10% were low-income families in a school made up of 35% low-income families, it’s an opportunity to improve. There may be barriers to access or something about the way the event is designed that is preventing or discouraging low-income families from attending.

The next step would be to connect with some of these families with a learning mindset to find out how their specific needs could be met in a way that works for them and to better prepare students for success.

Online databases like The Civil Rights Data Collection can provide data to answer questions of equality in education like:

-

What proportion of students who were suspended or expelled are individuals with disabilities, compared to overall enrollment?

-

What proportion of students who are enrolled in Advanced Placement classes are English Learners, compared to overall enrollment?

-

What proportion of students who are in Gifted and Talented programs are Black, Hispanic, Asian, or another racial minority?

Ideally, these proportions should reflect the overall enrollment. These are the types of questions that can lead to the discovery of opportunities to improve equity.

Common areas for equity improvement include:

-

Math achievement affected by SES: A student with low socioeconomic status (SES) in the U.S. is almost four times more likely to be a low mathematics achiever than a student with high SES [35].

-

Rates of reading failure worse for low-SES and English Learners: Seventy-nine percent of students from low-income families and 90% of English Learners cannot read at a basic level by 4th grade, whereas that number is only 65% over all categories of learners [36].

-

The pandemic exacerbated reading achievement gaps: Elementary students at the end of the 2020-21 school year were on average four months behind in reading compared to pre-pandemic scores. Students in majority-Black schools and students in predominantly low-income schools both ended the school year six months behind in reading [37].

Making reaching out easy with our Reaching Out guide

2. Build a strengths-based mindset

Equity is as much about mindsets as it is about outcomes. According to the University of Southern California’s Center for Urban Education, equity-mindedness means “the perspective or mode of thinking exhibited by practitioners who call attention to patterns of inequity in student outcomes” [38].

The idea is that outcomes will change if systems and processes become more equitable. As non-profit advocacy organization Education Trust puts it: ”Beliefs and language about students and their families shape how adults view and teach their students and interact with their families” [39].

One important mindset is the strengths-based, also known as asset-based, mindset. According to NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, “[a]n asset-based approach to education is key in achieving equity in classrooms across the country” [40]. This is in contrast to a deficit-based approach, which focuses on what is lacking or needs improvement.

In working to support students and families through an equity lens, it’s important to think about the contributions, strengths, and lived experiences of those with whom we work. Using words like disability, disadvantaged students, under-resourced families, even time-pressed to describe students and families may seem harmless. But this framing keeps the focus on what they don’t have or how they’re not enough.

Shifting language like disadvantaged to traditionally underserved invites us to ask: What can educators and other adult stakeholders do to better serve all students? Changing the way we speak can change the way we think, and what we think affects what we do.

From Learning Loss to Accelerating Learning

As educators began to grapple with the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, the term “learning loss” became commonplace to describe what students missed due to school closures and illness. However, while the normal trajectory of learning was certainly interrupted, it’s not the case that students stopped learning completely. According to an article from CityYear [41], “…students honed other skills, including flexibility, resilience and creativity. They mastered online classrooms and chat boxes. They figured out how to access homework assignments and ask questions during distance learning. Some students discovered they liked online learning even more than in person instruction.”

Learning is a dynamic, complex, process. To focus on what was “lost” can undercut the value of what students accomplished during a period of disruption and change. Instead, many strengths-based mindset advocates encourage using the phrase “accelerating learning” to avoid negatively describing a whole generation of students.

As Ron Berger of EL Education and Harvard Graduate School of Education put it in his article for The Atlantic [42] about a year after schools closed, “If districts focus too much on remediating “learning loss”—holding kids back a grade, categorizing students according to their deficits, and centering lesson plans on catch-up work—the students who have experienced the most trauma and disconnection during the pandemic may be assigned to the lowest level and most stigmatized groups. They will be viewed as deficient, and the inequities in place before and during the pandemic will be further amplified.”

Another important aspect of equity that’s related to the strengths-based mindset is rethinking sources of knowledge. Expertise lies within families and communities, as well as with education professionals. Wisdom and even solutions to equity-related issues can come from the experiences and stories of families.

Additional Resources

Understanding Equity

-

- Office for Civil Rights

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation

- The National Equity Project

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson

- Guiding Principles for Equity in Education by McGraw Hill

- Educational Equity: What does it mean? How do we know when we reach it? from the Center for Public Education

- Equity Audit from Mid-Atlantic Equity Consortium (MAEC)

Family Engagement for Equity

-

- “Building Powerful Partnerships with Families” by Dr. Karen Mapp

- “Evolving Together Towards Equity: Journeying from Family Involvement to Asset-Based Family Engagement” from the Wisconsin Dept. of Public Instruction

- Strategies for Equitable Family Engagement from OESE

- Embracing a New Normal: Toward a More Liberatory Approach to Family Engagement by Karen L. Mapp and Eyal Bergman, published by the Carnegie Corporation of New York

Data

3. Strive for Diversity and Representation

Research shows that student outcomes improve when students see themselves reflected in all aspects of their educational experience. For example, having just one teacher of color from kindergarten to third grade can boost academic achievement, high school graduation rates, and college enrollment rates for students of color [43, 44]. However, while half of all K-12 students enrolled in public schools are students of color, only 18% of the educator workforce is made up of people of color [45].

Representation includes staff, curriculum and community leadership. Students thrive when they read books written by authors representing the same diversity we value in this country. For the same reason, the historical figures students study should show diversity in gender identity and remove the predictability of success or failure associated with any social or cultural factor. According to one former language and composition teacher who now reviews equity-based initiatives, it’s about inclusion — whose voices are heard and which perspectives are brought in [46]. Such changes to an educational program can be difficult to make, but they can go a long way in improving the academic experience and school culture.

To increase the number of teachers of color who are recruited, some schools and districts use “grow-your-own” programs, which focus on recruiting from within the community and begin preparing future teachers while they are still in high school [47].

To learn more about what research has shown about the impact of educator diversity on student outcomes, see this simple fact sheet from IES: Black teachers improve outcomes for Black students [48].

4. Embrace More Sources of Knowledge

Educators are responsible for extensive subject matter expertise, which can make it easy to overlook other voices and resources when working to solve challenges in a classroom setting. Two under-utilized sources of knowledge are families and community based organizations.

Families have an incredible wealth of knowledge about the students your team serves. Whether its identifying the root cause of a child’s behavioral issue or understanding why a student is negatively responding to a learning activity, families are often the first and best source of essential information. Cultural, emotional, physical, or psychological barriers may be invisible to an educator or school leader but easily identified by a caregiver.

However, strategies for engaging with families can be a barrier to success when seeking collaboration. Investigating how schools approach families, what feedback opportunities are created, and whether schools are unintentionally signaling that family knowledge isn’t valued are important steps to ensuring educators get the information and insights needed.

Similarly, community based organizations can often provide a wealth of information and resources when serving specific sub-populations. Ilana Steinhauer, Executive Director Volunteers in Medicine (VIM) shares, “It’s easy to forget the importance of collaboration because everyone is so busy and so overworked and we just miss out on this huge opportunity to be one community working together.”

Footnote References

[1] Simón C., Barrios Á., Gutiérrez H., Muñoz Y. Equidad, Educación Inclusiva y Educación para la Justicia Social. ¿Llevan Todos los Caminos a la Misma Meta? Revista Internacional De Educación Para La Justicia Social. 2019;8:17. doi: 10.15366/riejs2019.8.2.001.

[2] Hatch T., Hill K., Roegman R. Instruction, equity, and social networks in district-wide improvement. J. Prof. Capit. Commun. 2019;5:72–91. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-07-2019-0018.

[3] Maloney T., Hayes N., Crawford-Garrett K., Sassi K. Preparing and supporting teachers for equity and racial justice: Creating culturally relevant, collective, intergenerational, co-created spaces. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2019;41:252–281. doi: 10.1080/10714413.2019.1688558.

[4] Center for Education Policy Analysis. Stanford University. https://cepa.stanford.edu/topic-areas/educational-equity

[5] Coleman, V. & Kimitto, S. “Educational Equity: Identifying Barriers and Increasing Access.” American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Equity.pdf

[6] “Definitions of Key Terms.” National Association for the Education of Young Children. Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity/definitions

[7] “Putting and Keeping Equity at the Center in Education: During COVID-19 and Beyond” Mid-Atlantic Equity Consortium. Retrieved from https://maec.org/resource/putting-and-keeping-equity-at-the-center-in-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond/

[8] “Striving to achieve equity is integral to WestEd’s mission.” WestEd. Retrieved from https://www.wested.org/equity/

[9] “Equity.” National School Board Association. Retrieved from https://www.nsba.org/Advocacy/Equity

[10] (Feb 2018) “States Leading for Equity: Promising Practices Advancing the Equity Commitments.” Council of Chief State School Officers. Retrieved from https://www.ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2018-02/States%20Leading%20for%20Equity%20Online.pdf

[11] “Head Start Promise.” National Head Start Association. https://nhsa.org/

[12] Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). “Kerner At 50: Educational Equity Still a Dream Deferred.” Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/kerner-50-educational-equity-still-dream-deferred?gclid=Cj0KCQjwnP-ZBhDiARIsAH3FSRclVDF1lbBEbLSfiqgdc6sTW-gYRb8PtSn4YQdCiYB4mXxsVcI7KsYaAstpEALw_wcB

[13] (23 Aug 2022) “Adverse Childhood Experiences.” National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/adverse-childhood-experiences-aces.aspx

[14] “NAFSCE Policy Work.” National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement. Retrieved from https://nafsce.org/page/PolicyCouncil

[15] Image from Medium https://medium.com/@CRA1G/the-evolution-of-an-accidental-meme-ddc4e139e0e4

[16] “Family Engagement Defined.” NAFSCE National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement. Retrieved from https://nafsce.org/page/definition

[17] Bodenhausen, N. & Birge. “Family Engagement Toolkit: Continuous Improvement Through an Equity Lens.” WestEd and California Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.wested.org/resources/family-engagement-toolkit/

[18] National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments at American Institutes for Research. Retrieved from https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/training-technical-assistance/education-level/early-learning/family-school-community-partnerships

[19] “The Biggest Blind Spot in Education: Parents’ Role in Their Children’s Learning” https://www.the74million.org/article/the-biggest-blind-spot-in-education-parents-role-in-their-childrens-learning/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

[20] Fan, X. & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1-22.

[21] Hong, S. & Ho, H. Z. (2005). Direct and Indirect Longitudinal Effects of Parental Involvement on Student Achievement: Second-Order Latent Growth Modeling Across Ethnic Groups. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(1), 32

[22] York, B. N., Loeb, S., & Doss, C. (2019). One step at a time the effects of an early literacy text-messaging program for parents of preschoolers. Journal of Human Resources, 54(3), 537-566.

[23] Sheldon, S. B. (2007). Improving student attendance with school, family, and community partnerships. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(5), 267-275.

[24] Rumberger, R. W. (2012). Dropping out: Why students drop out of high school and what can be done about it. Harvard University Press.

[25] Jurado de los Santos, P., Moreno-Guerrero, A. J., Marín-Marín, J. A., & Soler Costa, R. (2020). The term equity in education: A literature review with scientific mapping in Web of Science. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3526.

[26] Board Policy No. 0535. “Race and Equity.” Tukwila School District. Retrieved from https://aasb.org/wp-content/uploads/TSD-Race-and-Equity-Policy-U.pdf

[27] Rutgers University Survey. Retrieved from https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/learning-at-home-while-underconnected/conclusion

[28] Perrin, A. (2022, May 11). Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2021. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved September 3, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/06/03/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2021/

[29] Pew Research Center. (2021, November 23). Mobile internet fact sheet. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved September 3, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

[30] Smith, Aaron. “U.S. Smartphone Use in 2015.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, Pew Research Center, 25 Aug. 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/.

[31] “Census Bureau Reports at Least 350 Languages Spoken in U.S. Homes.” (2015). US Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/archives/2015-pr/cb15-185.html

[32] Doss, C., Fahle, E. M., Loeb, S., & York, B. N. (2019). More than just a nudge: supporting kindergarten parents with differentiated and personalized text messages. Journal of Human Resources, 54(3), 567-603.

[33] Jin, S., Kim, P, Tran, D., Truong, G., & Welch, T. (2020). “Can we reimagine schooling together? Three approaches for creating justice WITH our communities.” https://medium.com/@apiaedleaders/equity-in-re-opening-schools-bcbfb9f85de5

[34] (2019) “New Report Calls for a National System to Measure Equity in Education, Identify Disparities in Outcomes and Opportunity.” National Academies. https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2019/06/new-report-calls-for-a-national-system-for-measuring-equity-in-education-identifying-disparities-in-outcomes-and-opportunity

[35] OECD (2006), Education at a Glance 2006: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2006-en

[36] National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2019) Retrieved from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading?grade=4

[37] Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, Ellen. “COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning.” McKinsey & Company, 27 July 2021. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/covid-19-and-education-the-lingering-effects-of-unfinished-learning

[38] “Equity Mindedness.” USC Center for Urban Education. https://cue.usc.edu/equity/equity-mindedness/

[39] “Seizing the Moment: Race Equity Mindsets, Social and Emotional Well-Being, and Outcomes for Students.” Regional Educational Laboratory at WestEd. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/west/relwestFiles/pdf/Seizing_the_Moment_Participant_Webinar_Slides_508.pdf

[40] (29 Oct 2018) “An Asset-Based Approach to Education: What It Is and Why It Matters” https://teachereducation.steinhardt.nyu.edu/an-asset-based-approach-to-education-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters/

[41] (4 Aug 2021) “Why We Don’t Use the Term ‘Learning Loss.’” City Year. https://www.cityyear.org/national/stories/education/why-we-dont-use-the-term-learning-loss/.

[42] Berger, Ron. “Our Kids Are Not Broken.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 20 Mar. 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/03/how-to-get-our-kids-back-on-track/618269/.

[43] Dee, T. S. (2004). Teachers, race, and student achievement in a randomized experiment. Review of economics and statistics, 86(1), 195-210.

[44] Gershenson, S., Hart, C. M., Hyman, J., Lindsay, C., & Papageorge, N. W. (2018). The long-run impacts of same-race teachers (No. w25254). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[45] New England Secondary School Consortium Task Force on Diversifying the Educator Workforce. (2020) “INCREASING THE RACIAL, ETHNIC, AND LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY OF THE EDUCATOR WORKFORCE: A CALL TO ACTION FOR LEADERS.” Retrieved from https://www.greatschoolspartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DEW-FINAL-REPORT-12_20_r.pdf

[46] Education Development Center (2020). “3 Ways Schools Can Support Racial Equity.” Retrieved from https://www.edc.org/3-ways-schools-can-support-racial-equity

[47] Institute of Educational Sciences, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. (2017) “Strategies for Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating Grow-Your-Own Teacher Programs for Educators.” Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/northwest/pdf/strategies-for-educators.pdf

[48] Institute of Educational Sciences, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. “Educator Diversity Matters.” Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/northeast/pdf/REL-NEI_Educator_Diversity_infographic.pdf