By Maren Madalyn, contributing writer

In my second year as a mental health counselor, I worked one-on-one with a unique kid that I’ll call Oliver. Oliver and his mother had lived through very challenging situations outside of school by the time his case was assigned to me. For the two years before our introduction, Oliver worked with external services that helped him make huge strides with his mental health and emotion regulation abilities. It was now my responsibility to support him to reintegrate into a general education class and to help his academic skills catch up with those of his peers.

As a second grader, Oliver was on grade level when it came to mathematics, his favorite subject. He was also sociable and made friends easily, though we often practiced calm-down strategies when his feelings became overwhelming for him. Overall, both his teacher, Mrs. Egula, and I thought that Oliver seemed ready for second grade.

But past traumatic experiences outside of the classroom took a severe toll on his foundational reading skills. Oliver’s comprehension skills and fluency in reading were still at a kindergarten level, while his classmates were making rapid advances well above that. On top of this, I recognized that his growing resistance to books was quickly becoming a new trigger for him emotionally.

The previous year, while working in another special education classroom, I collaborated with a teacher who introduced me to the practice of multisensory teaching — using sensory experiences as part of a student’s learning. Ms. Hannah had diligently wielded all kinds of multisensory learning tools like air writing, sand writing, letter tiles, picture association, and other hands-on activities for students involving the senses to build reading skills.

In the general education setting, Mrs. Egula and I both were eager to explore how multimodal instruction might help Oliver master the fundamentals of literacy. We already knew that kinesthetic coping strategies were immensely powerful for his emotion regulation. This kid LIVED for the class weighted blanket, wobble chairs, and a unique physical activity we called “Bouncing Ball of Light” where he would simply bounce up and down in place until his internal ‘ball of light’ settled down.

Was it possible that adapting reading instruction using kinesthetic methods could help Oliver improve his literacy skills?

In the end, the answer was yes — but it would take more than a purely multisensory teaching approach at school to unlock Oliver’s literacy potential.

The power of a multisensory learning experience on literacy

Before we continue with Oliver’s story, let’s clarify what “multisensory teaching” is and what it offers to all learners.

What does “multisensory teaching” mean, anyway?

Multisensory teaching refers to methods of instruction for students that engage multiple senses in the learning process. For example, a teacher might use tools such as felt or magnetic letters in a tactile activity with a student, engaging both touch and sight senses to help a child build their letter knowledge.

Though it is commonly used to support literacy development, classroom teachers can also employ multisensory activities in math instruction to support kids with dyscalculia. For this article, let’s focus on multisensory teaching techniques aimed to boost literacy.

A key driver behind multimodal instruction is the idea that it benefits students who struggle with more ‘traditional’ methods of teaching. For children with dyslexia in particular, multisensory learning techniques offer great potential to support their reading journey.

Below are a few examples of inputs and outputs used in multisensory teaching for literacy:

- Auditory input includes having students hear letter sounds, words, sentences, and stories read aloud. This auditory input reinforces phonics and reading comprehension.

- Visual input includes having students see letters, words, sentences, and stories using visuals like pictures, charts, and flashcards. This helps students recognize patterns in words and build sight word vocabulary.

- Kinesthetic input includes having students manipulate letters and words physically, like tracing letters with a finger and building words with letter tiles. This links motor skills to the reading process.

- Tactile input includes having students trace letters and words with texture, like sandpaper or shaving cream. The tactile sensations reinforce letter formation.

- Verbal output includes having students practice their letter sounds out loud or read passages aloud. Producing the verbal output helps cement learning.

Multisensory learning in students applies at multiple ages and grade levels. Especially in the early childhood setting, a multisensory teaching method can help prepare young learners to become confident readers later in the classroom setting. This matters because preparation for literacy is part of overall kindergarten readiness, which is critical for longer-term student outcomes beyond the classroom.

Does multisensory learning actually work?

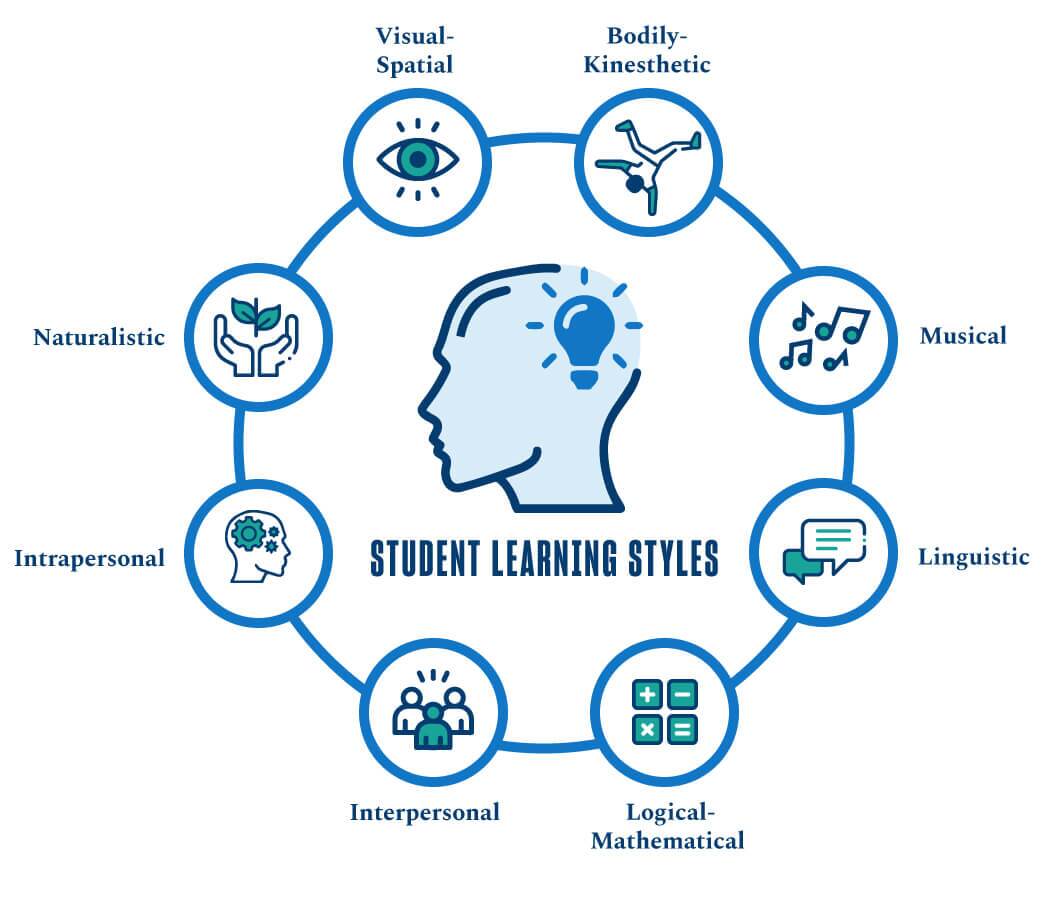

A traditional approach to reading instruction might suit some students well, but as any educator can verify, not all students learn new skills in the same way. The multisensory approach is unique because it activates different parts of the human brain simultaneously to enhance learning and memory (Sarudin et al, 2019). In other words, a teacher can adapt multisensory approaches to reading instruction to meet students’ diverse learning styles, such as tactile learning or kinesthetic learning.

Multisensory teaching offers students a different way to build foundational literacy muscles, like word and sentence decoding skills, that empower them to become confident readers. For example, ‘sky writing’ involves a student spelling out a word by drawing the letters in the air as they sound them out. This kinesthetic method of learning builds muscle memory associated with each auditory part of a word, which is immensely helpful for students with learning styles relying in part on body movement.

It’s critical to understand that, in the research world, the jury is still out on whether matching activities with learning styles tangibly improves learning. However, educators benefit from having a variety of teaching strategies available to support their students’ academic skills development — especially with literacy.

It’s also important to understand that multisensory activities work best when integrated with other methods of literacy instruction, not as a replacement. It should complement and enhance explicit teaching. Additionally, multisensory teaching is more impactful when it is adapted to each student’s needs. What works for one student may not work for another. Last — and this is true for many approaches to literacy instruction — multisensory lessons that follow a logical sequence and structure to layer on phonics instruction and other aspects of reading are more likely to be successful in supporting student learning

In summary, an intentional, structured integration of multisensory experiences into other teaching methods can reinforce the specific literacy concept being taught. Rather than using it in isolation, this method of teaching offers educators the opportunity to create multifaceted approaches to build foundational reading skills.

What does research tell us about the impact of multisensory teaching?

Before we can answer this question, let’s take a quick detour to understand the connection between multisensory teaching and the science of reading, a term increasingly used among educators today.

Though commonly misunderstood as a curriculum, the science of reading is a critical body of scientific literature that informs educators’ understanding of what does and doesn’t work with teaching literacy. This research is essential to guide educators in delivering effective instruction that cultivates basic language skills, phonological awareness, and other core aspects of reading in children.

So what does science tell us about multisensory teaching for literacy?

In short, it’s complicated. Some studies indicate that multisensory language instruction combined with other reading interventions can greatly help with teaching literacy skills to dyslexic students or those at risk of dyslexia (Hall et al, 2022). Others show a more mixed result with employing multisensory learning techniques with dyslexic students (Schlesinger & Gray, 2017).

Nonetheless, for kids that face challenges with reading, a multisensory learning experience can be one of several aids available to educators to bolster their literacy development.

Curiously, for kids without diagnosed learning differences, multisensory teaching may also offer benefits to their reading skills. For instance, one study found a positive effect on reading skills when teachers use a multisensory technique to teach open syllables to preschoolers (Rostan et al, 2020). However, researchers still recommend that educators avoid over-emphasizing any one approach to phonics instruction and other early reading skills development. This includes multisensory approaches, especially as the scientific community deepens its understanding of effective teaching practices.

In sum, learning how to read is complex, and there isn’t just one pathway to this destination. The beauty of this journey is that educators have a plethora of tools available to guide future readers on their path forward, and they can experiment to find which method of teaching works best for their students.

At the same time, these evidence-based insights underscore the importance of equity in education — when teachers adapt any aspect of instruction to meet the unique needs of a given student, many other students also stand to benefit. Multisensory instruction techniques for literacy could indeed support many students in becoming stronger, confident readers.

Multisensory activities for the classroom

Multisensory teaching comes in a variety of forms. The core principle behind any multisensory instruction asks educators to engage students in all of their senses — to cultivate learning through smell, sight, sound, touch, and even taste.

One of the most common approaches to literacy instruction that uses multisensory lessons is the Orton-Gillingham method of teaching. This approach is a direct, explicit, multisensory, structured, sequential, diagnostic, and prescriptive way to teach literacy when reading, writing, and spelling do not come easily to individuals.

Its principles for reading instruction underscore a wide variety of programs designed for structured language teaching with a multisensory lens. For example, the intensive Wilson Reading System incorporates elements of the Orton-Gillingham method into its structured literacy curriculum that leverages multisensory techniques geared toward dyslexic students.

When I think back to my time in Ms. Hannah’s special education classroom, I recall witnessing a wide variety of multisensory methods. She used kinesthetic activities, auditory techniques, and visual teaching methods to expose her students to phonics instruction in every sense. Each of these class activities informed my and Mrs. Egula’s approach to boosting Oliver’s literacy.

I mentioned a few of these approaches already, but here are a few more examples of hands-on activities in a multisensory toolkit:

- Wikki Stix Letters: Students create letter forms and words by molding and arranging Wikki Stix.

- Letter Sort: Students sort tactile letters made of various materials, alphabetizing them while speaking each letter aloud to build recognition of letter-sound relationships.

- Phoneme Manipulation: Students use magnetic letters on whiteboards to add, delete, or substitute phonemes to make new words.

- Sound Ball Toss: Students say a letter sound when catching a ball, then blend sounds to make a word.

- Movement Breaks: Students build literacy and motor skills as they walk, hop, or move like a word while spelling it aloud.

- Sensory Bins: Students search for items in bins representing a certain letter pattern, like “soft c” or “long o”.

- Colorful Semantics: Students color-code parts of speech and semantics in sentences.

- Auditory Bombardment: Students listen and verbally repeat recordings of vocabulary, passages, or rhymes.

Each instructional activity enables students to see, say, hear, and manipulate letters and words, enhancing literacy, learning, and memory. When combined with other methods of instruction, students can expand their vocabulary development, comprehension skills, and other essential aspects of reading.

Here’s an activity we adapted to support Oliver with his phonemic awareness using Play-Doh balls. After helping him recalibrate to the idea that Play-Doh wasn’t just for recess, I coached Oliver to create little balls of dough, which he then squished as he sounded out each phoneme in visual word cards I held. It took some time, but soon Oliver was quickly recognizing more words and sounds during our 1:1 reading time.

These unique class activities helped Oliver gain confidence in his reading. But Mrs. Egula and I knew that there was much more that we could do to support him — that there were other players on Oliver’s learning team that could change the entire literacy game for him.

Family engagement: bringing multisensory learning home

As much progress as Oliver made in the classroom through multisensory learning techniques and instruction, his success with reading depended on his family’s active engagement in his learning.

Let’s clarify what I mean by family engagement. My favorite definition comes from the National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement (NAFSCE):

“Family engagement is “a shared responsibility in which schools and other community agencies and organizations are committed to reaching out to engage families in meaningful ways and in which families are committed to actively supporting their children’s learning and development.”

When I hear the phrase “shared responsibility”, I think of partnership, one of the essential principles of any effective family engagement program: families are contributing and valued partners on the learning team enabling a student to thrive. When schools collaborate with families as true allies, it unlocks a whole new level of support for each student’s literacy journey and other academic outcomes.

Four family-friendly activities for multisensory learning at home

Family engagement in multisensory teaching doesn’t require a parent to be physically present in the classroom. Families also don’t need to become experts in instructional methods like the Orton-Gillingham approach to understand its potential benefits, either.

How then do educators support families to leverage the elements of multisensory instructional techniques at home with their students?

ParentPowered has worked with hundreds of organizations to amplify their family engagement strategies geared towards literacy development, math skills, social-emotional learning, and much more. We believe in the power of creating everyday learning moments for families that fit into existing at-home routines — and we have the research to prove that this method works!

Below are just a handful of example messages from our ParentPowered programs, offering multisensory approaches to thousands of families via text message each week. Each fun activity complements in-classroom literacy instruction, ensuring that their child grows into a confident reader. Share them with your families and fellow educators!

For Infants:

Families can use multisensory techniques to plant the seeds for their child’s future success in literacy, even when they’re as young as 3 months. This activity uses auditory cues to encourage infants to talk and repeat words.

- FACT: You can do little things every day to help your baby learn to say words – like encouraging your baby when your baby is trying to talk and repeating words.

- TIP: When your baby points to you and says “mmmmm,” respond with: “Yes. I’m mmmmamma. Mama.” Then chant the word “mama, mama” as you point to yourself.

- GROWTH: Keep helping your baby say words! Now try repeating words. As you hand your baby an object, repeat its name again and again: Cup, cup, cup.

For Toddlers:

Designed for 1- and 2-year-old children, this activity combines imaginative play with auditory and kinesthetic actions to teach fundamental skills like listening, essential for long term reading development and much more.

- FACT: Games that require your toddler to follow directions build their listening and comprehension skills. These are key skills for learning and growing.

- TIP: Play a silly direction game at bedtime. Hold a favorite stuffed animal. Ask, “Can you tickle teddy bear’s ear? Can you tap his tail? Wiggle his foot?”

- GROWTH: Keep playing direction games! Now play with the covers. Ask, “Can you put the covers over your toes? Can you put them over your tummy? That’s silly!”

For PreK:

This tactile activity is an excellent way to help PreK children practice their letter knowledge as well as early writing skills.

- FACT: In kindergarten, children will write their name on many things. You can help your little one get a jump-start on this big exciting literacy skill.

- TIP: Before bed, invite your child to use their finger to write their name on your back. Have them name each letter out loud.

- GROWTH: Keep writing! Ask your child to draw a picture and sign their name. Can they name each letter as the write it? Hang it up where everyone will see it!

For Kindergarten:

This fun activity combines auditory and kinesthetic cues to help kindergarteners get familiar with recognizing syllables in words. It’s easy for families to play this game on a daily basis with their little learners!

- FACT: Words have different beats. There are short words like CAT (1 beat) and long words like CRO-CO-DILE (3). Clapping the beats helps kids sound words out.

- TIP: As you fill the tub, say, “Let’s clap the names of things we see, and count how many beats. SOAP (1 clap), WA-TER (2 claps), SHAM-POO (2 claps).”

- GROWTH: Keep clapping out the beats in words. At dinner, clap the names of things you see around you: BOWL (1 clap), NAP-KIN (2 claps), SIL-VER-WARE (3 claps).

For Elementary School:

Perfect for second graders, this listening activity helps kids recognize the units of sound in words, helping them decode unfamiliar words with the same units into management chunks. This skill is essential for a student’s lifelong vocabulary development.

- FACT: Listening for sounds in words builds the skills kids need to sound words out. Sounding words out is a key step to reading more challenging words.

- TIP: Play “Listen & Step” before bed. Say, “Listen for the /sh/ sound like the /sh/ in dish. If you hear it step to bed.” Try words like fish, shell, and push.

- GROWTH: Keep listening. Now use words that have a /sh/ sound and some that don’t. Say, “Only take a step when you hear /sh/ .” Try shop, dish, wash, boat

Looking for more fun ways to engage students’ senses in literacy development? Explore ParentPowered’s family workshop library for more inspiration and videos like the ones below:

Multisensory teaching can help readers at school and home

The more educators and families collaborate, the more students thrive.

Oliver’s second-grade reading journey ended on a positive note. Around her busy schedule, Oliver’s mom led her son through body movements connected with words during their walk to school, sounded out letters on packages at the grocery store, and drew out words on the steamed mirror after bathtime. Little by little, activity by activity, Oliver’s reading skills and confidence in his abilities increased.

The combination of family engagement activities at home and multisensory teaching combined with direct instruction in the classroom elevated Oliver’s literacy by a full grade level by the time summer arrived. Though he still had a ways to go, his entire learning team — his mom, Mrs. Egula, and I — were incredibly proud of the strides he made.

And that’s how family-school partnerships make learning possible!

About the author

Maren Madalyn has worked at the intersection of K12 education and technology for over a decade, serving in roles ranging from counseling to customer success to product management. She blends this expertise with fluid writing and strategic problem-solving to help education organizations create thoughtful long-form content that empowers educators.